Lugares de interés (POIs) del Mapa

0: Target - North Dock Target

Más sobre Target - North Dock Target

2: Target - North Sands Yard

while another son, Joseph Lowes, took over the yard at North Sands in 1860 and changed the company name

to J L Thompson. Robert Thompson Jnr’s yard closed in 1933. J L Thompson’s yard was closed in 1979,

although the fitting out quay was used by Doxford’s and Laing’s. St Peter’s Campus of Sunderland University

now stands on the site.

Más sobre Target - North Sands Yard

7: Target -Greenwell and Sons

Más sobre Target -Greenwell and Sons

10: Target - Wearmouth Colliery

Más sobre Target - Wearmouth Colliery

11: Target - Laing and Sons (Deptford Yard)

renamed Sir James Laing and Sons. Laing’s merged with Thompson’s

and Sunderland Forge in 1954.

Más sobre Target - Laing and Sons (Deptford Yard)

13: Target - Short Brothers

other yard. It closed in 1964 when the firm was unwilling to redevelop and build bigger ships. The yard was

demolished, although Bartram’s took over the fitting out quay, which was still in use in the 1980s.

Más sobre Target - Short Brothers

16: Target - Pickersgill and Sons

Miller, Rawson and Watson. The firm split in 1845 and Pickersgill

opened a yard at Southwick. During World War II, Pickersgill’s

took over the neighbouring Priestman yard. The company

merged with Austin’s in 1954 and the Southwick yard was

redeveloped at a cost of £3 million. The yard closed in 1988

Más sobre Target - Pickersgill and Sons

17: Target - Doxford and Sons (Pallion Yard)

Más sobre Target - Doxford and Sons (Pallion Yard)

18: Target - Priestman and Co

Más sobre Target - Priestman and Co

19: Target - Swan Hunter and Wigham Richardson

The company has effectively ended all shipbuilding and is now concentrating on ship design with just under 200 people employed.

Más sobre Target - Swan Hunter and Wigham Richardson

21: Target - William Gray and Company

Más sobre Target - William Gray and Company

22: Target - Short Brothers

Más sobre Target - Short Brothers

28: Target - Bartram and Sons

Más sobre Target - Bartram and Sons

30: Atkinson Road

16th May 1943 Atkinson Road and Rosedale Terrace Corner. One Parachute mine dropped, demolishing 4 houses leaving 44 seriously damaged and a further 102 damaged. 10 people were killed, 2 seriously injured and 6 slightly injured. The gas and water mains were also fractured.

Más sobre Atkinson Road

31: Atkinson Road

Number 48 Atkinson Road bombed at 12:50 on the 15th August 2004, no one was injured

Más sobre Atkinson Road

32: Binns

10th April 1941 Binns stores on both sides of Fawcett Street were almost completely destroyed by incendary bombs. No one was injured.

Más sobre Binns

33: Brandling Street

4th May 1941, Brandling Street. One heavy calibre High Explosive bomb demolished 3 houses, seriously damaged 33 and slightly damaged another 10. Nine people were killed in this attack, two were seriously injured and one slightly injured.

Más sobre Brandling Street

34: Central Station

0113 hours, 6th September 1940. Direct hit by two H.E. bombs. Crater 30ft across and 15ft deep. Note carriage thrown across platform by blast

Más sobre Central Station

35: Central Station

6th September 1940, Sunderland Central Station. Damage caused by two High Explosive bombs. No one was injured.

Más sobre Central Station

36: Cleveland Road

The result of a small bomb dropped in Cleveland Road on the night of 7th April 1941. Luckily no one was hurt.

Más sobre Cleveland Road

37: Church Walk

24th May 1943, Church Walk. One 500kg High Explosive bomb was dropped leaving a crater 60 feet across and 12 feet deep. No one was injured , 5 houses were seriously damaged, a further 10 were damaged along with 6 shops and 1 public house. Gas, water and electricity mains were interrupted.

Más sobre Church Walk

38: Corporation Road

11th October 1942, Corporation Road. One 500kg High Explosive bomb landed in the centre of the roadway leaving a crater 36' by 12' deep. The bomb demolished part of a school and five houses, 20 houses were seriously damaged and a large area of residential property affected. Seven people were killed and 21 seriously injured (including a special constable proceeding to duty) 54 people were slightly injured. Gas, electricity and water suppleis were affected.

Más sobre Corporation Road

39: Cromarty Street

4th May 1941, Cromarty Street. One High Explosive bomb near Redby School caretaker's house. 4 houses demolished, 6 seriously damaged, 25 slightly damaged, gas main fractured. Caretaker and his wife came out of debris almost uninjured.

Más sobre Cromarty Street

40: Duke Street North

Más sobre Duke Street North

41: Farringdon Row

7th November 1941 Electricity Works Farrington Row. One High Explosive bomb direct hit on a boiler house leaving a crater 30 feet across and 15 feet deep. Note the gantry on the right of the photograph, a man was standing on this when the bomb exploded but only suffered from slight shock.

Más sobre Farringdon Row

42: Fulwell Road

7th November 1941, 96-98 Fulwell Road. A direct hit by one High Explosive bomb causing a crater 15 feet across and 15 feet deep. 3 Cottages were demolished, 2 seriously damaged and 6 slightly damaged. One person was killed, 2 seriously injured and 4 slightly injured. Several people were trapped in the debris but were rescued later.

Más sobre Fulwell Road

43: Fulwell Social Club

1st May 1942, Fulwell Road Social Club. One High Explosive bomb at south east corner leaving a crater 32 feet across by 8 feet deep. The end of the club was demolished and two people were killed in Mayswood Road

Más sobre Fulwell Social Club

44: Fulwell Quarry

28th August 1942. Eight incendary bombs of 50kg Phosphorus-oil type were dropped in fulwell quarries. This photograph shows the parts making up one such bomb

Más sobre Fulwell Quarry

45: Ferrys Farm

1st May 1942, Ferry's Farm Sea Road. One High Explosive bomb hit the farmyard causing a crater 28 feet across and 10 feet deep and serious damage to farm buildings as shown. No one was injured, one of the carts in the background was thrown by the blast over a hen coop but chicks and hens were unhurt.

Más sobre Ferrys Farm

46: Hillfield Gardens

27 August 1940, High Explosive bomb, direct hit, no-one injured

Más sobre Hillfield Gardens

48: John Street

2345 hours. 14th March 1943. John Street shows damaged office type property on the west of John Street . The vicar of St. Thomas Church was standing here and was buried in the debris and killed

Más sobre John Street

49: Josephs Toy Shop

Más sobre Josephs Toy Shop

51: Lodge Terrace

Más sobre Lodge Terrace

52: Newbridge Avenue

Más sobre Newbridge Avenue

53: Mayswood Avenue

Más sobre Mayswood Avenue

54: Portobello Lane

Más sobre Portobello Lane

56: Roker Avenue

7th November 1941 Roker Avenue. One High Explosive bomb hit the corner of the Blue Bell hotel demolishing it. The crater was 25 feet across and 15 feet deep, damage was caused to gas and electricity mains. One person in the street nearby was killed, others were trapped in the cellar but were successfully rescued.

Más sobre Roker Avenue

57: Roker Baths Road

Más sobre Roker Baths Road

58: Sea Road

1st May 1942, field situated south of Sea Road. High Explosive bomb in foreground leaving a crater 24 feet across by 6 feet deep. The crater at Fulwell Social Club is just behind. No one was injured but the effect of these bombs seriously damaged 4 houses and slightly damaged 53 others

Más sobre Sea Road

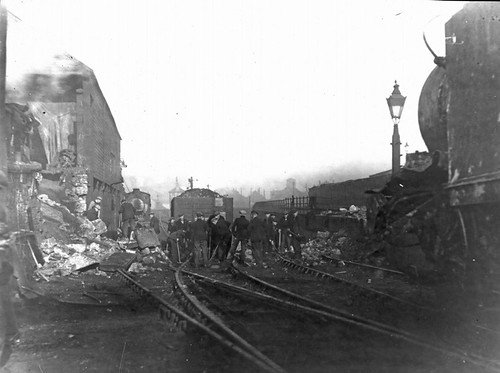

59: South Dock

7th November 1941 London North East Railway (LNER) sidings South Docks. One High Explosive bomb fell upon one of the lines. The engine shown on the right was approaching the spot just as the bomb fell. The blast lifted the engine from the rails and turned it at a right angle and damaged the front wheels. No one was injured.

Más sobre South Dock

60: St Thomas Street

2345 hours, 14th March 1943. St. Thomas Church. John Street. One parachute mine on corner of church demolished the west half and caused serious damage to the property. Crater 15ft across and 8ft deep. Note girder thrown to foreground. Collective damage to these two mines, 7 houses destroyed, 359 damaged, 566 shops were damaged 9 other buildings seriously damaged , 35 untenable.

60 damaged, Gas, Water and Electricity affected.

8 persons killed, 9 seriously injured, 31 injured

Más sobre St Thomas Street

62: Southwick Playing Fields

30 September 1941 Corporation Playing Fields, Southwick. One High Explosive bomb making a crater 48 feet across by 10 feet deep, slight damge to adjoining greenhouses. No one was injured

30 September 1941 Corporation Playing Fields, Southwick. One High Explosive bomb making a crater 48 feet across by 10 feet deep, slight damge to adjoining greenhouses. No one was injured

Más sobre Southwick Playing Fields

65: Train Crossing

The Civic Defence Report states "0215 hours, 16th May, 1943. Fulwell Crossing. One Parachute Mine fell on railway crossing, severed the line. Crater 25ft. across 10ft. deep. Serious damage to property of wide area. Two persons serously injured and six slightly injured."

Más sobre Train Crossing

66: Tunstall Vale

2047 hours, 23rd February, 1941. 5 Tunstall Vale. One person killed and one seriously injured in house No.7 shown on left of photogaph

Más sobre Tunstall Vale

67: Tunstall Vale

2047 hours, 23rd Feburary 1941. 3 Tunstall Vale. One H.E. bomb between number 3 and number 5. 3 persons killed and one seriously injured, extracated from debris and flooring shown below fireplace in photograph. A baby was found the next morning practically unhurt.

Más sobre Tunstall Vale

68: Victoria Hall

Más sobre Victoria Hall

69: Waterloo Place

16th May 1943, Waterloo Place Monkwearmouth, One 1,000 kg and one 250 kg High Explosive bomb dropped causing craters 35 feet across and 25 feet deep and 18 feet across and 8 feet deep respectively. 15 people were killed, 5 seriously injured and 6 slightly injured. 8 houses and one public house were demolished, gas and water supplies were also affected.

Más sobre Waterloo Place

71: Zealous

5th June 1942. One High Explosive bomb fell into the river, striking the rack bouys as it entered the water, about 0800 hours the same day this bomb exploded doing damage to the aft end of the steam ship "Zealous". Four men on board were slightly injured, and one man was seriously injured. A similar bomb which fell nearby exploded a few minutes previously and slightly damaged another ship.

Más sobre Zealous

72: Augustin Preucil - Usworth Air Field

Augustin Preucil was a Czech pilot who was a spy for the Germans.

For more details please see the BBC news story

Más sobre Augustin Preucil - Usworth Air Field

73: Cyril Barton V.C

was an English recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces.

He was 22 years old, and a Pilot Officer in the 578 Squadron, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve during the Second World War when the following deed took place for which he was awarded the VC.

On 30 March 1944 in an attack on Nuremberg, Germany and while 70 miles from the target, Pilot Officer Barton's Halifax bomber was badly damaged by enemy aircraft, losing an engine. A misinterpreted signal resulted in three of the crew bailing out, and Pilot Officer Barton was left with no navigator, bombardier or wireless operator. He pressed on with the attack, however, releasing the bombs himself. On the return journey, as he crossed the English coast, the fuel ran short and with only one engine working he crashed trying to avoid the houses and pit head workings of the village of Ryhope and was killed. One miner died, when he was hit by part of the crippled plane, but the remaining three crew members survived.

Más sobre Cyril Barton V.C

74: A Teenager in Sunderland

When the War broke out there was panic in our street. We thought the German bombers would be flying straight across the North Sea — my mother made us all get under our beds. We soon had an air raid shelter made in the back garden and our next-door neighbours would come in as soon as the air raid siren sounded. It was bitterly cold and we were all frightened hearing the bombs dropping. We could often spend many hours in the shelter but we still had to carry on with our daily work. I was working in the Power Petroleum Company at Roker, Sunderland as a junior typist. I cycled to work each day and we had to carry our gas masks with us at all times. One day I arrived at work without my gas mask — I was terrified but didn’t dare tell anybody. I just kept glancing at the clock and was so thankful when it was my lunch hour. I cycled as fast as I could up Roker Avenue and across the town, right along Thornholme Road to my home in Braeside. After a quick drink of water I grabbed my gas mask and cycled all the way back to work.

It was most uncomfortable in the air raid shelter and my sister Joan and I were always covered with flea bites. We longed for a cup of tea but often Mother had used the tea ration. My father was warden for Braeside and many men walked up and down the streets making sure everyone was alright. My father had many friends.

Everything was rationed. One day somebody said Woolworths had knicker elastic — there was a stampede — we could each buy one yard.

Very occasionally there would be bananas for sale — you could stand in a long queue for two or three bananas but it was worth the wait. Bananas were kept for children only. What I wanted most of all was a Fry’s Sandwich Bar. I still wonder at all the things in the shops now.

I will always remember the night a bomb landed on the railway station in Sunderland — the explosion blew the wheels of a carriage right out of the station and through Mr Joseph’s shop window. The Victoria Hall was also bombed — Joan and I were terrified.

I had a younger brother who was only seven when the War was declared and my aunt also had two young sons. She hired a taxi to take them all to the County Durham village of Eggleston, where they were evacuated for just a short time. My aunt was very unhappy and the boys were not learning anything at the village school. Another aunt suggested they all went to Maltby, a small town near Rotherham where she was a head teacher. When my brother Philip started school there the teacher asked him his name and he replied Philip Maltby — the teacher told him to hold out his hand and she caned him. Philip was a dear little boy and he always had a smile.

When I was eighteen, in 1942, I joined the Royal Air Force and spent five wonderful years. What an experience. I had to report to an airfield in Gloucester but had never been further than the County Durham town of Barnard Castle. Everybody in my hut smoked — thank goodness I wasn’t tempted. At the end of the War I was posted to Germany. Although we were forbidden to speak to the people we were polite to the children and gave them our sweet ration.

Betty Sutherland (nee Maltby)

Más sobre A Teenager in Sunderland

75: A Child at War

I was a young lad of 9 years when the war started. I am now 74 years and I can honestly say that in all my life I have never experienced a more exciting time than those few years between 1939 and 1945.

My family situation at the start of the war found me part of a one parent family - Dad had been called up. I had two younger brothers, one aged 3 years and the youngest was 1 year old. Mum was in her late thirties and we lived at 11a (mum wouldn't have 13!) Dykelands Road Fulwell, Sunderland. My Gran lived in number 9 three doors away with my uncle Harold and Grandad Nevison. Grandpa was a grounds-man at Usworth Aerodrome and uncle Harold drove a lorry with corn and animal feed stuffs from Fulwell Mill. He was in big demand on the Home Front not only as a distributor of food and provisions but he also doubled as an ambulance driver. On the day of my story he had a brand new Morris Commercial parked outside gran's at number 7.

It was a Friday, we were having lunch, it was a pretty meagre affair using some of yesterday's leftovers warmed up and made into a kind of broth. Mum had a funny feeling, and come to think of it so did I. She said "I feel as if something is going to happen". If she had mentioned premonition I wouldn't have understood, or even took any notice, oblivious as I was, with my eyes glued on a comic stuck up against the sauce bottle. I was alway's getting wrong for that! Then it happened:

That lunchtime the sirens went at the same time as the modulating drone of a bomber was heard. In no time at all mum ushered us out of the house and into the Anderson Shelter at the bottom of our small back garden. The Ack-Ack (anti-aircraft guns)had already opened up as we crash-dived into the shelter. Mum drew the wooden door shut and we were plunged into darkness. No time to light the candle.

The sound of exploding shells rose to a crescendo and suddenly there was another sound that made us all cling to each other. A high pitched whistling sound which got louder and then I heard nothing. The exploding bomb deafened me with a pressure on my eardrums that I have never felt since. There was a rushing wind and the shelter door blew off. Stuff began to shower down outside, first the big stuff, broken bricks and tiles, then dust and soot.

Mum said it's over, thank God. We clung together for a long time and my ears put themselves right. "I heard the Warden shouting is everyone ok?"

Más sobre A Child at War

76: Ryhope Hospital

It was around this time that I met my future husband. He was among many wounded soldiers who were patients at Ryhope Hospital. Gradually the war progressed in our favour, and by 1944

German prisoners were also treated at the Hospital. Many of the shops in Sunderland were gone due to the heavy bombing. Dawdon pit pulley wheels, located on the cliff edge, were a landmark target for the German bombers. Clothes could only be had with the appropriate vouchers. Women would queue outside the Butcher’s for hour for half a rabbit. My Father was still abroad on duty but we received our mail quite regularly. It was only after several years of the war ending that things eventually got back normal.

Más sobre Ryhope Hospital

77: Moreland Street Roker

I lived with my parents, brother, and two sisters in Moreland Street Roker Sunderland. My father worked at the Fulwell Road Bus Depot, in his spare time was a keen model maker He had just finished a Model of a Lancaster Bomber, which was his pride and joy.

This model had pride of place in the house. It stood on a round table in the centre of our living room.

One night my father was on night shift at the bus depot when he saw what was called a Purple in the sky. This was a circular movement in the sky made by a searchlight before the siren was sounded and was used to indicate that an Air Raid was imminent. On the night in question my father saw the Purple and immediately came home to collect us all, and to take us to the bus depot where there was a good Air raid shelter. Before we left the house it was my job as the eldest child to collect the “Deeds Box” which was a biscuit tin containing the deeds to the house and other important documents. While we were in the shelter an incendiary bomb was dropped on our house, it went through the roof, through the ceiling of our living room and demolished the model Lancaster on our living room table, together with half the table, then through the floorboards and into the foundations. My uncle who had served in the Great War was in the house at the time and had refused to come with us to the shelter saw that the bomb in the foundations had no exploded.

He got out of his chair and quickly got a spadeful of coal dust from the coal house and covered the bomb with it.

My father’s model was completely destroyed, but I still have the table today only now it’s a semi circular one.

Más sobre Moreland Street Roker

78: George Street East

I was aged eight and a half at the start of the war. My Father, aged thirty five, was sent to work in a sugar beet factory in Yorkshire. For this he was paid 18-6d per day for a twelve hour shift along with £I.4s per week lodging allowance. He could travel home on a travel warrant once every three weeks. I was second eldest in a family of seven. We lived in 5 George Street East in Silksworth, opposite the Miners’ Hall. We attended St Leonard’s Catholic school. Before he left for Yorkshire my father built an Anderson shelter in our garden. I can’t ever remember using it. Instead we would go under the stairs or under the table in our home. The shelter was used as a gang hut; we even tried cooking chips using a candle in the Anderson.

When the sugar beet season was over my father returned home. He was told there was a job available in Erdington, Birmingham, which he took. This paid £16 a week. Here he made friends with “Tot” Jopling, originally from Hordern. Late in 1941 the whole family moved to Erdington where we moved in with Mr and Mrs Jopling, their eight children and two lodgers. Luckily they had a three-storey house, which was in Cecil road. While the railways were delivering our furniture and personal effects I noticed a female railway worker opening our chest of drawers. Later my mother found some of our clothes were missing. The Police were called in and the girl’s home was searched. Our missing clothes were found. She later went to court and I was awarded one shilling for being vigilant. We got our own home in Cecil road. The children younger than fourteen went to St Mary and John’s school in Gravelly. My elder brother was sent to St Thomas’ at the other end of the village. Earlier my mother had sent six of us to the cinema at Silksworth for a total cost of fourpence; in Erdington it cost us fourpence each.

During the war shopping became quite an experience. We were rationed, which meant each person was allowed a limited amount of items. This included foodstuff such as fat, tea and bacon. The points system was in operation, with tinned fruit costing extra. It was possible to get clothing vouchers from Irishmen who went home to Southern Ireland to get their own clothes.

After two years in Cecil road we were offered a three-bedroom house in Erdington. This was owned by the Catholic Church. After his shift at work my father was required to do extra hours “Firewatching.” Once or twice he brought home parts of incendiary bombs. At this time coal was very scarce. We were able to get to fuel from Aston Gas Works. Every Saturday morning from 9am to 12pm people were allowed ¼ of a cut of coke. My father took my brothers Jim, Harry, Donald and myself to the gasworks. We left home at 5 am and walked to the works, which usually took one hour. We were never first in the queue. Once we had the coke, Harry and Donald were sent home on the tram, whilst Jim and I, along with my father, pulled the fuel home on a summer sledge.

Clothing coupons were used to obtain shoes as well as clothes. Unfortunately, however, I wore out my shoes so quickly my parents decided I would have to wear clogs.

Aged thirteen I became a paperboy. I delivered mornings, evenings as well as Sunday mornings. I was paid 13s/6d. My employer gave me all the Sunday papers and magazines that he could not sell. These I took up to the army camp in Erdington to sell and I was allowed to keep all the profit for myself.

Two days before VE day I started work myself at ICI in Witton Birmingham. I cycled five miles to to get there and my working week was 47 hours. I was paid £1-2s-8d. We were given two days off for VE day.

Más sobre George Street East

79: Hendon

Day in the Life of a Nine Year Old

Author — Raymond Hall Davison

The year is 1941, I am 9 years old. It’s a late autumn evening and we are sitting at the fireside waiting for the sirens to inform us that the German bombers are on their way.

At prompt 10 o’clock the sirens sound and off we go into the brick shelter in the yard. Dad, my uncle and myself go into the back lane to meet the other neighbours for a chat. Total darkness.

Suddenly we hear the drone of the German bombers approaching the town. We hesitate. Out of the darkness the sky is brilliantly lit up. Scores of searchlights roam the skies looking for German planes. Suddenly the ack—ack guns commence firing. The noise is frightening but exciting. I have on my tin helmet as shrapnel begins to drop from the sky. Now the bombers are overhead, we race to the air raid shelter.

Tonight they have decided to drop incendiary bombs. I rush into the yard with Father and Uncle to find that three of these bombs have fallen into the yard and are sprouting flames. We manage to douse the flames with a stirrup pump, which has been issued to every household. We are lucky that no incendiary bombs have fallen on the house itself. What an exciting night it has been. 4 a.m. and we are just going to bed.

I get up very early the next morning so that I can collect as much shrapnel from the street. I know that my pal who lives three doors away will be planning to get out before me.

I arrive at school feeling very tired after having such an exciting night. We have one hour’s gas mask practise and finish school at lunchtime.

It’s a lovely afternoon. My pal and I decide to play quietly in the street. Suddenly a German fighter, flying low over the coast to avoid the radar screens, machine guns the streets. Because of the low flying there has been no air raid siren warning. What an exciting day so far.

It has been a beautiful day, sunshine all day, and it is going to be a clear starlit night. This means, almost certainly, that it is going to be a long night of death and destruction. Sure enough, at about midnight, the sirens sound the alert and hordes of German bomber planes arrive over the town.

Here we go again!

Más sobre Hendon

80: The village prepares for war

Hopefully, it’s my one and only boast that at the time of my eighth birthday in August 1939, I knew the names of both the German and Italian foreign ministers. Perhaps more importantly, I was aware of the enormous problems that their countries were creating in both Europe and Africa.

At home,::text like most other local mining families, we read the Daily Herald, where pictures of Herr Von Ribbentrop (Germany) and Count Ciano (Italy), who was Mussolini’s son-in-law, often appeared on the front page. They would be shown standing alongside their counterparts in embassies of neighbouring capitals, London included. Inside Germany, Ribbentrop’s leader, Herr Hitler, as he was best known then, was almost worshipped. Elsewhere, he was regarded with the deepest suspicion, even held in fear. This man was dangerous.

As well as the Daily Herald, we had just acquired our first wireless set, a Bush by make, and the novelty of listening to its news bulletins and musical programmes had far from faded. Indeed, we thought that the sun shone from the BBC! The Bush Radio Company had engaged a well-known radio celebrity of the day, Christopher Stone, about who I knew something for he was featured in a series of cigarette cards, to promote sales. In the same set, there were cards of Charlie Kunz, Sir Adrian Boult, Freddie Grisewood, Norman Long, Stuart Hibbert, Lew Stone, Peggy Cochrane, Roy Fox, the two Leslies (Sarony and Holmes) and Harry Roy. In radio-shop windows, Christopher Stone was pictured alongside an owl perched on top of a Bush wireless. The slogan read, ‘A Wise Bird Settles on a Bush.’ We were staunch CWS patrons, but I’m sure that Bush radio came from Palmers, the large Sunderland furniture, cycle and radio store, and was probably paid for at half-a-crown a week. We had no electricity and power came from a large dry battery and an accumulator, which we took to the CWS for re-charging. When a valve became defective not long after the war began, we waited for over a year for the store to obtain a replacement! It was the way of things and the domestic front was pushed into second place by the war.

Visits to the Hippodrome also brought further chances to keep abreast of international affairs. There were always ten minutes of Movietone News and meetings of Neville Chamberlain with Hitler figured prominently at the time of the Munich crisis in September 1938. We did not barrack the German dictator then, but once the war was underway, our boos took off the roof!

In line with every other community in the land, New Silksworth was filled with a sense of foreboding. When Munich turned sour, it was clear that war was almost a certainty. Minds were focused and it was now full-steam ahead to prepare to defend ourselves.

Again, cigarette cards proved helpful. One issue in particular, Air Raid Precautions, gave useful hints on how to deal with incendiary bombs, using a scoop with an elongated handle, once the sirens had sounded and the searchlights were probing the night skies. There were tips, too, on how to fit and adjust gas masks, as well as making shutters to keep in the light during the blackout. For the staff of the Sunderland Rural District Council, then our local authority, there was much midnight oil to be burned. Here was a situation of unprecedented magnitude. Unlike the 1914/18 War, the Germans now had aeroplanes capable of hitting targets anywhere in the United Kingdom and the provision of an air-raid shelter for every family was a major priority. For those homes with a garden, a steel corrugated unit, known as an Anderson shelter, was provided by the Government. A deep hole needed to be dug to accommodate it. Where there was no sizeable garden, or non at all, Warwick Terrace, Somerset Cottages, and Margate Street, for example, brick shelters with reinforced concrete roofs were erected in the back yards.

In addition to the weekly Sunday afternoon walk that we made to the Weightman Memorial Hall, opposite the former Recreation Ground, for Sunday School lessons, an additional visit, this time in mid-week early in 1939, was required. The purpose was to have our gas masks supplied and fitted. Packed into a cardboard box, they had to be carried everywhere once hostilities were underway. For those who lived in Tunstall Parish, the Miners’Hall was the issuing depot.

Of equal importance to the gas masks and the air-raid shelters, was blackout. Here, there could be no half measures, either. How true it was, I cannot say but the claim was that a German pilot would see the light created by a smoker’s match in the streets thousands of feet below! What I do know is that dads had to employ what woodworking skills that they had to put shutter frames together. Miles of black curtain material were on sale in shops to avoid the dreaded Air Raid Warden’s call of ‘Put That Light Out!’

There was no 11th hour peace settlement and I heard the news of Germany’s invasion of Poland on Friday, 1st September 1939 outside of Questa’s ice cream parlour in Blind Lane on my way home to Newport. Two days later my dad hobbled out on his crutch as we played in the street to tell us that we were at war with Germany.

New Silksworth and the world would never be the same again!

Más sobre The village prepares for war

81: No Custard

At a much higher social level, the writer, Kingsley Amis, had a similar dislike to dining out. When I heard him interviewed on radio some years ago, the reason he gave for preferring meals at his own table was that he lost the right to pour if he was out of the house!

I would not be much more than eleven when the opening of the British Restaurant in the bottom house of Tunstall Terrace gave me a chance to spread a wing and have a first meal in public. These restaurants were a well-meaning innovation and much welcomed by a war-weary public. Lord Woolton was Minister for Food at the time and what made them so attractive was that they were non-profit making, while an added bonus was that food was served for which you did not require coupons. The result was that the rations at home were helped go further.

The system known as rationing had not been introduced at the outbreak of war in 1939, but the rate at which the German U-boats began to sink our merchant vessels made it unavoidable eventually. My dad welcomed the move. It meant that food, albeit less than what we were used to, was assured for every citizen. Without rationing, the rich would have eaten, while the poor, and that was us at the time, would have gone hungry. Every family in the country was issued with ration books, depending on the number of adults and children, and had to be deposited at a shop of the family’s choosing. Some registered with the Co-op, but others at corner shops, possibly because the chances were better there of a bit of what was known as under-the-counter food becoming available from time to time! At every weekly shopping, coupons, sometimes known as points, were removed from the book, while certain pages were overprinted with indelible pencil. It was a fair-share-for-all arrangement in theory and the Duke of Northumberland in his Alnwick Castle home would be entitled to exactly the same amount of food per week as the poorest-paid Northumberland collier. The Act provided for one ration book per person and no more.

Our local authority of the day, the Sunderland Rural District Council, was responsible to the Ministry of Food for the conversion of the Tunstall Terrace house to a restaurant for public use. It was hardly an ideal property and today’s Health and Safety Inspectors would have given it a low mark, but it was centrally situated and easy to get to. There was no neon strip lighting outside, simply a wooden notice board signifying that this was a British Restaurant. The cooking took place on the ground floor, while the two upstairs rooms, in which generations of mining families would have slept over the years, was the dining area. At the foot of the stairs sat a cashier, who exchanged your money for two plastic tokens of different colours. With one, you would be supplied with a first course, usually boiled potatoes, meat and a vegetable. The other was needed for a dessert, one of which was, for me, the strangest of combinations - milk pudding and custard! Apple pie with custard, but never a rice pudding!

Not having eaten a meal in a public place before, but encouraged by my mam to give the restaurant a try, I recall a very nervous entry and a distinct feeling of unease at having to share a table with strangers, The world and his wife, and that included some of our teachers, were on the premises, while the queues, the limited space, clouds of steam equivalent to today’s saunas rising to the ceiling, did not make for the happiest of experiences. The staff was composed of women, who I had heard my dad refer to after he had come home from the Labour Party and Parish Council meetings. They were all what were known in the village as big Labour Women, not because of their stature, but due to their fervour for, and loyalty to, the Socialist cause. It would be a tiring shift that they had to work.

Because of the setting and its limitations, few would leave feeling that they had had their best meal ever! It was a no-win situation, really, and light years away

from Mengs, Carrick’s, The Barnes or Milburn’s. Whether it survived until the end of the war, I cannot say, but in places where they did, and Stafford would be one, they became known as Civic Restaurants. Some years later, on our way from the R.A.F. station there to watch Wolverhampton Wanderers play, we stopped for a Saturday lunchtime meal of fish and chips. How relieved I was to see that there was no milk pudding with custard on offer! No, thanks!

Más sobre No Custard

82: Mulgrave Street

I was five years old when war broke out in September 1939 and I was just about to start Stansfield Street School. Dad was working at JL Thompson’s shipyard as a labourer. We lived in Mulgrave Street Monkwearmouth so he didn’t have far to go. He was an ARP. Warden and it was his job (along with many others) to go into the streets after dark to check everyones windows for signs of light that were shown through the black coloured blinds that everyone had — they were a must, in case the light was spotted by any German aircraft as they made their way across. Dad would shout up at the windows and if there was no answer, he would walk along the dark passages and give a knock on the door’ just to let them know, or, as the case may be, shout up the stairs, then wait for a reply.

A bomb dropped on JL Thompson’s shipyard and as it was just at the bottom of our street my parents thought some of the houses had had a direct hit, as the noise was quite near. After the all-clear we made our way out of the air raid shelter. Dad opened the kitchen door (sitting room) only to find the windows had been blown out by the blast from the bomb. There was glass everywhere. I remember him saying, “Thank God the house is still standing” and Mam began to cry. It didn’t take long before the windows were replaced on which a criss-cross pattern was made from a roll of sticky paper, which served as a protection for the rest of the war.

When the sirens sounded at school we were quickly taken down into the shelter, which was underground, singing along with the teachers to Ten Green Bottles Hanging on the Wall. I remember it as if it were yesterday.

People couldn’t go far as some of the picture halls were closed down and the beaches were barbed-wired off. The only entertainment was the wireless and the pubs of course, if and when they could afford it. Making clippie mats was very popular with the whole family being involved. We children would sit on Mam’s shiny fender or Dad’s homemade crackets and with a progger each, were there until time for bed.

Church street library where people would spend a little time going through the books looking for something to read, must have been a great comfort for the people. As Dad would say,” It broadens the mind”.

I was eleven years old when the war finished - the excitement of it all, ships’ buzzers sounding off, flags strewn across the streets from one window to another, men, woman and children all cheering and dancing. What a memory. Later on came the street parties - big wooden tables pulled together and white cotton sheets were used as tablecloths - everything was hand-made. Servicemen were coming home this time for good.

Things started to get back to normal - blackout blinds came down, sticky paper removed from the windows, although it was no easy task. Picture halls opened and the barbed-wire was taken from the beaches after the sand had been cleared of any bombs that may have been dropped. The lamps were lit again and gas masks were given in - freedom at last! Then as time went by the end of the ration books.

By JOAN QUINN.

Más sobre Mulgrave Street

83: A bomb falls on Monkwearmouth

There were events I can recall happening during the 1939-45 War. I can remember the first time the sirens sounded declaring the outbreak of war, it was on a Sunday dinner time, and my mam had asked me to go a message to Meggie Rowe’s. I was crossing the street at the time when the sirens sounded, and on my return asking my mam what was wrong, she explained the reason for the siren, which over the next few years would be a regular sound. One day my pals and I were all playing around the steps to the ‘File Factory’ offices in Richmond Street, when all hell let loose, it was a daytime raid. The big anti-aircraft gun based in the L.N.E.R stables in Easington Street facing Richmond Street (the building is still there today) opened up firing at enemy aircraft that was dropping its bombs, one hit ‘Alibabas’ sauce factory, which was situated in the middle of Richmond Street. Just seconds before this Mr Day who lived in number six and his son Derek, who was one of my pals, came rushing out gathered us all together and ushered us through the passageway of his house to the air raid shelter. We only just made it into the passage when the bomb hit, all the back windows of the house were blown out while the front windows were left intact. Mr Day kept us all calm and had been our Guardian Angel. The Germans had a few attempts at our locality obviously trying for the ships in the river, Wearmouth Colliery and the railways, hitting the aforementioned sauce factory, the railway bridge over North Sheepfolds road and the colliery yard. They actually dropped a bomb in the pit pond that was home to lots of goldfish, but the bomb never exploded. The enemy also set fire with incendiaries to the Monkwearmouth Rail Goods Yard, but the worst raid was the Bromarsh Cinema on the end of the bridge, where a lot of lives were lost.

Más sobre A bomb falls on Monkwearmouth

84: Childhood Memories

Everyone was supplied with gas masks. My mam took me somewhere down High Street Bank to, I think Hudson Road School, to be fitted with a gas mask as there were various sizes. I can still remember the smell of the rubber, which I didn't mind at all. We were given cardboard boxes to keep them in. It was slotted with string so it could be carried at all times round our necks. People used to make each other gas mask covers for Christmas presents, in all sorts of materials.

Every night my mam would have everything ready just in case we had to get up and go to the air raid shelter. As soon as the sirens went to warn us there was an air raid she would wake me up and I would jump into my siren suit, which as a bit::text like a cat suit with a hood and just put it over my pyjamas. She would also have a blanket and pillows and a flask of tea and some sandwiches as we never knew how long the raid would last.

We lived in Bedford Street and had a very big back yard. We were advised by the War Department that an air raid shelter was to be erected in our yard but we would not be able to use it as it was to be allocated to the admiralty who were billeted in the Grand Hotel in Bridge Street. We had to run up to the top of the street to an underground shelter under the National and Provincial Bank, Timothy Whites, and Taylors (a chemist). When you went in there were a number of rooms with bunk beds three high so we could sleep in them. We used to play games and tell stories and sing. The sound of the sirens used to (and still does) send a chill down my spine.

I remember one night, the sirens went and, as we were running up the street to the shelter, the guns were firing and searchlights caught an aeroplane in its sights. We kept dodging into the doorways until we reached the shelter.

One raid I remember was when St. Thomas's church in John St. was hit and the vicar was killed in the blast, which was so bad that it blew the fire watches in the air raid shelter and all the dust came down. All the bottles in the chemist's shop shattered and we could smell all the chemicals from the bottles. I remember our king and queen coming to visit the bombsite in John Street.

I became ill and developed diphtheria. I was taken to Havelock Hospital, which was an isolation hospital and I wasn't allowed any visitors because of infections. When there was an air raid in hospital the nurses would put the wooden trays, which had legs, over our heads to protect us from any glass from the windows. That was a particularly hard winter and I remember mam and dad only able to get the tram to Kayll Road and having to walk the rest in deep snow.

When I started school I used to take the tram from outside St. Mary's church in Bridge Street to Redby School. Every Friday we were allowed to take a toy. One day I took a doll and the sirens went, so were were ushered into the shelter and I dropped and broke my doll.

One day we were sent from home from school as a bomb had dropped on the Fulwell railway crossing and a number of houses had been bombed and the families killed.

My dad worked at the North Eastern Marine on the docks as a boiler maker and plater, and if there was a raid, the bridge would be turned, and as the men wouldn't be able to get off they had to wait until the raid was over.

War became a way of life. We were given instructions on how to tackle fires. We were supplied a stirrup pump and instructed how to use it. We all had ration books and were allocated a small amount of food each week; it didn't seem to stop us from managing a family party on New Year's Eve. We had a big table, which would extend to seat about thirty people and we would have a wonderful time. Everyone would do their party piece and my cousin would play the piano. My family had a coffee stall in Park Lane and many of the soldiers who were based on the parks would often come to the stall for tea and pies, etc. We got to know some of them quite well, so they were invited to the New Year's party. I remember one of them had a kilt and one of my uncle's swapped his trouser's with the soldier and proceeded to dance round the table singing 'We Are The Boys Of The Old Brigade' with everyone else following him and singing too. These were wonderful days.

As the war went on I felt we would win as we used to listen to Mr Churchill as he gave the country the will to fight and I felt safe in his hands. We would listen to Lord Haw Haw and laugh at the things he said as we knew they were all lies.

As the war in Europe was coming to an end, Mam took me to visit my Aunt Dolly who lived in Sussex. We decided to go to London for the day and the day we went was V.E. Day. It is a day I will never forget. Everyone was was happy and dancing and singing. We went to Buckingham Palace and saw our Royal Family on the balcony and we all cheered. What a wonderful day.

Darren49 WW2 People's War

WW2 People's War is an online archive of wartime memories contributed by members of the public and gathered by the BBC. The archive can be found at bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar

Más sobre Childhood Memories

85: Ryhope Hospital

Soldiers wounded at Dunkirk had begun arriving in Ryhope where the huts next to Cherry Knowle had become a military hospita. Wounded soldiers wore light blue uniforms and soon became a famila sight in the streets. My uncle Jack Dolan was in the Pioneer Copr. but was stationed at Chalks farm. He hurt his side when he fell off the anti-aircraft gun and he to ended up in Ryhope hospital, I think he enjoyed being mistken for a Dunkirk Hero.Jack Blackburn

Más sobre Ryhope Hospital

86: No Evacuation

I was born in 5 Charles Street Monkwearmouth.After one heavy raid we cam e out of th eshelter to find that Charles Street had been bombed and our house was wrecked. My mam and I spend hours trying to recover our possessions. All the ceilings were down, the windows and doors blown out and the gas had to be turned off.

Más sobre No Evacuation